Re-reading Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale! In act 4 scene 3, we meet… the king of thieves!

The previous scene established that we’re in Bohemia know, caught us up on some characters, and set up some plot. And now Autolycus struts out on stage. Who is this? The character is described as a rogue in the text, with the Folger footnotes calling him a con man. The Winter’s Tale is a fantasy play, and Autolycus brings the magic simply because he’s a figure from mythology, a demigod even. Ovid’s Metamorphosis, allegedly one of William Shakespeare’s favorite books from his childhood, has a lengthy description of Autolycus as the son of Mercury a.k.a. Hermes. Autolycus is described is having Mercury’s great speed, but also able to cast illusions and make people see whatever he wants them to see. This made him the greatest of all thieves. The king of thieves, you might say.

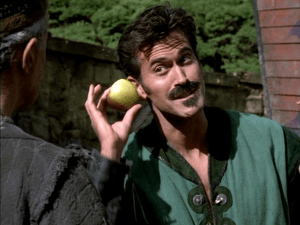

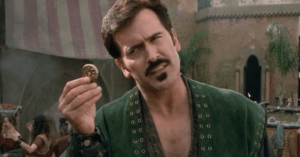

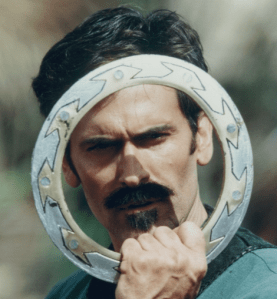

Who am I kidding? You already know all about Autolycus because you’ve seen Xena: Warrior Princess. So, let’s go there! The Xena version of Autolycus, played by the great Bruce Cambell, is often a buffoon, making it up as he goes along. But at other times, he can walk the walk with cool moves and lots of James Bond-like gadgets. At the end of the day, Autolycus is one of the show’s heroes. He has a heart of gold when it comes down it, and he famously refuses to kill. The crossover with The Winter’s Tale is that both versions have a lot of clever wordplay and a sense of being unpredictable. For many years, Bruce Campbell has been a supporter of the big Shakespeare shows up in Portland, so he must be familiar with Shakespeare’s Autolycus.

Getting back to The Winter’s Tale, Autolycus enters with a song. Like Shakespeare’s rhyming dialogue, everyone has their opinion about how songs in these plays are supposed to be performed. Rather than debate about it, I say leave it up to each actor and director to figure it out for themselves. Autolycus’ song is about winter turning to spring, and how, in a roundabout way, this whets his appetite to commit thievery. He jokes about spending time with his aunts during springtime, and the Folger edition footnotes state that “aunts” in this context means sex workers. I’d love to know how the fine folks at Folger reached that conclusion.

Autolycus says he was formerly a servant of Florizell. He says his business is “in sheets.” By all accounts, this is impossibly not a double entendre, but him having recently been in the business of buying and trading linens of all kinds. But then he talks more about how “the silly cheat” is his real revenue, and how is goal is to avoid the stocks. (Not to get caught, in other words.) Autolycus also mentions his father, and says he was born under Mercury, as in the astrological sign and not the god. But I’d still consider this a shout-out to Ovid’s version.

The shepherd’s son returns to the scene, rattling off what’s basically a long grocery list of stuff his family wants him to get for an upcoming sheep-shearing fest. It’s a lot of twisty-turny wordplay, making the son quite a fool. (Remember that the Pelican edition names this character “the clown.”) There’s a mention of his sister, which we the audience know as Perdita. One big question here is, if it’s sixteen years later, how are portraying this character now? Are there ways to get this across with costuming and makeup? Was he a played by a kid in his earlier scene? Is he the shepherd’s adult son, and we’re trusting the audience to accept that time has passed? Despite the time passage, he acts like the same character as before, so maybe not a lot of change is needed.

Autolycus watches him in secret, making an insult that I don’t dare repeat here, and then he approaches the son, pretending to be a man who has just been injured in a robbery. Autolycus steals the son’s money. The stage direction tells us he does that, but not how. It’s up to each production. Unaware that he’s being robbed, the son offers to give Autolycus some of his money, but Autolycus makes a big deal about being so honorable that he doesn’t take any – even though he already has.

Autolycus tells the son that he was robbed by a man named… Autolycus! In doing so, he lays out his own backstory. Florizell threw him out of the court because of his vices. He then worked as a process server (which is apparently much the same thing as it is today), he was an ape trainer (!) and he put on a “motion,” meaning a puppet show, about the Prodigal Son. He even says that Autolycus is the one who put him in his clothes, which I suppose is true.

Autolycus also says he once went about with “troll-my-dames.” This is a reference to a board game better known as Troll Madam, or Pidgeon Hole. It’s pretty simple. There’s a board with holes along the bottom. Different holes have different point values, and players compete to flick marbles through the holes. The joke here is that the game is seen as something childish and frivolous, and not something you’d play at the prince’s court. A double meaning, however, could mean this refers to Autolycus’ womanizing ways, also frowned upon at court.

Autolycus miraculously recovers from his injuries, and the son wishes him well. All alone, Autolycus tells the audience that he will go to the sheep-shearing content, except that all the rubes there will be his “sheep” to steal from. He gives us one final verse from his song, about coming to a fence on a long journey, only to hop over it and keep going.

Next: Perdita’s deets.

* * * *

Want more? Check out my ongoing serial, THE SUBTERKNIGHTS, on Kindle Vella. A man searches for his missing sister in a sprawling city full of far-out tech, strange creatures, and secret magic. It’s a sci-fi/fantasy hybrid full of action, romance, mystery, and laughs. The first ten episodes are FREE! Click here for a list of all my books and serials.