Re-reading Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale! Here’s where we get into why so many consider the a “problem play.” Act 5 scene 3 is the big dramatic ending, yet it’s ambiguous and it happens so fast.\

All the main characters come onto the stage, and Paulina, in a roundabout way, welcomes everyone to her home. Remember that The Winter’s Tale was created for Blackfriars, an indoor theater, which allowed Shakespeare to do things like changes in location. So we’re in a place we haven’t been before, and Shakespeare felt it was important we know that because the dialogue emphasizes this. It’s odd that two kings are visiting this woman’s house. I guess we can assume all their soldiers and bodyguards and whoever else are stationed outside.

Based on the dialogue, Paulina’s house is one big art gallery. Leontes talks about walking through many “singularities” before reaching this room. My books’ footnotes say this means priceless works of art. But, if we’re imagining The Winter’s Tale retold as far-out epic fantasy (as I have been, on occasion) then this could mean something outrageous like portals into other worlds in place of paintings. Anyway, Leontes reminds everyone (and the audience) that they’ve gathered there because Perdita wants to see the statue of her mother Hermoine.

Paulina says the statue is as peerless as Hermoine herself was. She warns everyone to prepare themselves for how lifelike the statue is. Then we get the stage direction. In all my books, it’s written as “[She draws a curtain to reveal] Hermoine (like a statue).” My Pelican edition, however, has this stage direction: “[Paulina reveals] Hermoine [standing] like a statue.” I cannot say whether the brackets and parenthesis are a modern addition, but someone must have put them there for a reason. Like the “pursued by a bear” direction, here is Shakespeare getting specific with the stage directions. In the excellent documentary series Shakespeare: The King’s Man, host James Shapiro spends a lot of time on this, alleging that these are the most detailed stage directions among Shakespeare’s plays.

But anyway, Paulina reveals the statue of Hermoine. To us the audience, this is the actress playing Hermoine returning to the stage, but what is happening in the fiction of this scene? Aside from the bear, the statue of Hermoine is the definitive image of the play. Leontes is in awe of the statue’s realism, with an odd line about how she is “not so much wrinkled.” Is he saying she hasn’t aged, or is he acknowledging the passage of time? Who can say?

Perdita says she will kneel and pray before the statue, adding, “Do not say ‘tis superstition.” There’s a lot behind this phrase, as churches in England at the time were getting all snippy at each other, arguing that parishioners who kneel and pray in front of statues were committing idolatry. Perdita’s line is either a joke poking fun at this, or it’s a way of depoliticizing this issue, as if to tell the audience to relax about it.

While Perdita kneels and prays, Paulina says the statue is “newly fixed,” meaning that it either was recently made or recently put in this place. She also says, “the color’s not dry.” This is a reference to how all those ancient marble statues from Greek and Rome were originally painted with vibrant colors. My Folger edition alleges that this practice was also done to statues in Shakespeare’s day. What’s odd is that a lot of the artwork you see for The Winter’s Tale shows Hermoine as an all-white statue, as if carved from marble. I suppose some sort of visual is needed to get across the idea that she is a statue, whether through makeup and costume, or lighting and/or special effects. But everyone’s going to carry on about how lifelike she looks. How far you go in making Hermoine look like a statue versus merely looking alive again is up to each production.

Then there’s another specific stage direction, telling us that Leontes is crying. Camillo encourages him to let it all out, how sixteen years of sorrow led up to this moment. Polixenes admits to being the cause of Leontes’ pain, offering to take away Leontes’ grief if he can. But then, Polixenes refers to himself as “he” not “I” during this speech, so perhaps there’s some double-speak going on. “He” could also mean Leontes, suggesting that Leontes has himself to blame for his actions.

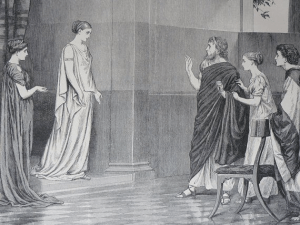

After seeing Leontes overwhelmed with emotion, Paulina wants to draw back the curtain and cover up Hermoine. Leontes urges her not to. This becomes a runner through the next part of the scene, as they repeat this exchange a couple of times in a row. What is Paulina up to? She brought everyone here to show off the statue, but now she wants to separate it from them all. I wonder if she’s toying them, because next she gives them a choice. Leave now, she says, or stay and behold more wonders. Paulina says she can make the statue move. She tells Leontes to “awake your faith” and the says that anyone who believes this is “unlawful business” should depart. No one does.

Then we’re in full-on magic/fantasy mode, as Paulina commands the statue to descend and “be stone no more.” We get yet another specific stage direction with “Hermoine descends,” and more marveling from the other characters upon seeing the statue come to life. There’s more magic talk as Paulina says, “Her actions shall be as holy as my spell is lawful.” That’s straight out of Dungeons and Dragons right there.

Leontes touches Hermoine and says, “She’s warm.” They embrace, with the other characters describing the affectionate intimacy of their embrace. Paulina has a comment about how anyone would laugh if they heard this story but did not see it. (A reminder that this is a comedy, perhaps?) Paulina wonders why Hermoine doesn’t speak, and she commands Hermoine to do so. She brings Perdita to Hermoine’s attention, saying the long-lost princess has been found.

I’ve found a lot of people online who are debating whether Hermoine actually speaks or not during this finale. But she does. All my books have her delivering the speech that follows. She speaks only to Perdita, wanting to know where Perdita has been and what her life has been like. Hermoine said the Oracle gave her hope that Perdita was alive. Flipping back to act 3 scene 2, this references the part of the Oracle’s statement that, “The king shall live without an heir if that which is lost be not found.” Hermoine concludes by saying that she “preserved” herself in the hopes that she’d someday be reunited with Perdita.

Okay, so what is happening here? Is this actual fantasy magic, in that Paulina somehow turned Hermoine into stone, hid her away, and then returned her to life at this moment? The text would seem to suggest that, but unlike A Midsummer Night’s Dream or The Tempest, magic has only been hinted at and not depicted on stage up to this point. In my research, I’ve found that some believe Hermoine faked her death and has been hiding with Paulina for sixteen years, and this “statue” business is some sort of ruse they’ve concocted for this moment. But, what purpose would that serve? Is this so Hermoine can assess their reactions to seeing her before she fully reveals herself? As with everything in this final scene, it’s wide open to interpretation, and it depends on how directors and actors choose to play it.

Paulina says there will be plenty of time for Perdita to answer Hermoine’s questions. She calls everyone “precious winners all,” and tells them to go forth and share their exultation with the world. She calls herself a “turtle,” meaning a turtle dove, as she plans to fly off and find a perch where she will spend the rest of her days lamenting her lost husband. (That would be Antigonus, who was… pursued by a bear!). Why a turtle dove? They allegedly mate for life (is that true?) and they’re traditionally seen as a symbol of long-lasting romance in marriage – hench “two turtle doves” in The Twelve Days of Christmas. But Paulina is a lone turtle dove, a sad image.

Leontes gives the play’s final speech. He recalls the comment from act 5 scene 1 about him not remarrying without Paulina’s direction, and now he makes similar promise to her, that he’ll find a man for her to marry. Some believe this means that there’s a romance between Leontes and Paulina in the works, but Leontes thanks her for returning Hermoine to him. Is Hermoine’s worldless embrace enough to communicate that she and Leontes are a couple again? It seems that is the intent, but I don’t know. Leontes says he won’t have to search far for a good man for her, and he offers her Camillo’s hand in marriage. As king, he can just do that. And I suppose this makes up for all of Camillo’s living in exile for sixteen years.

Leontes addresses Hermoine, who still doesn’t speak to him, saying he forgives her and Antigonus. Although he encourages the two of them to look upon each other, which is maybe a little odd. He reintroduces Hermoine to Perdita and Florizell (who has been in this scene the whole time but hasn’t spoken), telling her that her son-in-law is also heir to a king. He uses the phrase “troth-plight” to describe young lovers’ engagement, and I wonder if that also has some double meaning. He asks Paulina to lead them away from there, where everyone can tell their stories and answer each other’s questions. He breaks the fourth wall a bit, saying each one can “answer to his part performed.” Acknowledging that it’s all been a play. Shakespeare does this a lot in his plays, where the final speech reflects back to the story that just unfolded. Twelfth Night and the already-mentioned Midsummer Night’s Dream.

And that concludes The Winter’s Tale. My final thought is… dang it. DANG IT. Because reading this final scene, all I can think is, “I need to read this again.” Paulina emerges in these few pages as a main character, perhaps even the master manipulator behind it all. This means closer study of her journey through play is warranted. There’s also Leontes and Hermoine. Has Leontes truly had a change of heart? Are they truly reconciled? In my reading, most tend to summarize this as a happy-sad ending. Everyone is reunited, but they still have all the losses they’ve experienced. Is that enough?

This was supposed to be a fun and exciting trip through one Shakespeare’s most unusual works, but I’m left wondering about this ending. Clearly, The Winter’s Tale is over, but I’m not yet done with The Winter’s Tale.

Next: Take two.

* * * *

Want more? Check out my novel MOM, I’M BULLETPROOF. It’s a comedic/romantic/dramatic superhero epic! https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08XPXBK14.